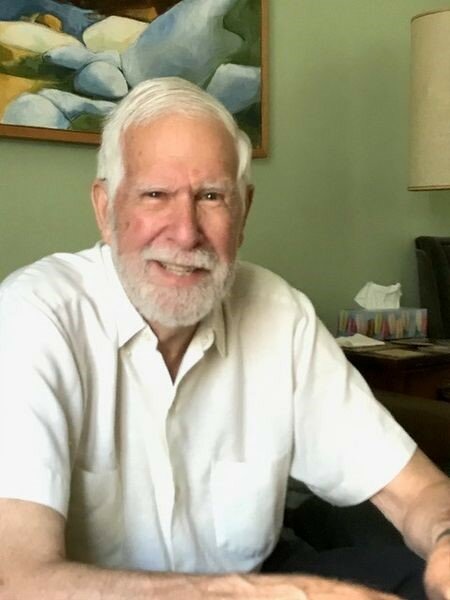

Celebration of Life

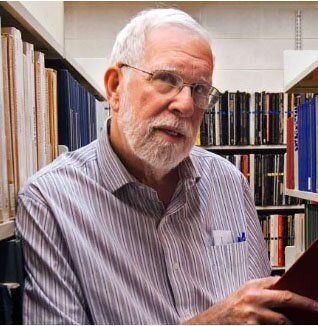

Obituary of Alan Stuart Ruffman

The following was originally published by Paul Wilson on January 19, 2023, as a special in The Globe and Mail, the original article can be found at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-marine-geologist-alan-ruffman-shed-new-light-on-several-historic/

In the late summer of 1963, Alan Ruffman, a third-year geology student at the University of Toronto, was returning to Canada from a student exchange program in Finland. Rather than fly home, he had talked his way onto an 800-foot grain carrier bound for Churchill, Manitoba, with a hold full of sea-water as ballast. Somewhere off Greenland the ship ran into a storm so violent it lost steerage and found itself turned back toward Europe, storm-tossed on the heaving surge of a following sea. Mr. Ruffman began to doubt the wisdom of his choice, but the storm finally subsided and the ship was able to resume its course. “It was a gift,” he said later. “The sea was dead calm and in full-moonlight we saw a small forest of tall, majestic, cathedral-hewn icebergs marking the entrance to Hudson Strait. That sealed my decision to enter graduate studies in Oceanography.”

Mr. Ruffman, marine geologist, civic activist, disaster historian, died peacefully at his home in Halifax on Dec. 28 at the age of 82. On graduating from the U of T in 1964, he moved to Halifax to study marine geoscience at Dalhousie University. Over the next six decades, Mr. Ruffman pursued a multi-pronged career as a freelance marine geologist and a prominent Halifax civic gadfly. He mapped features and anomalies on the ocean floor from the Arctic to the South Atlantic, and provided the surveys necessary to develop offshore resources like the Venture gas field off Nova Scotia or Hibernia off Newfoundland. He was a founding member of many local citizens’ groups, like the Ecology Action Centre, Friends of the Halifax Common, and Movement for Citizens’ Voice and Action. His “Jane Jacobs” moment came when he played a leading role in stopping the Harbour Drive proposals that would have run elevated highways through the heart of Halifax’s historic waterfront district.

David Piper, a marine geologist, member of the Atlantic Geoscience Society, and a long-time colleague, said that Mr. Ruffman became “a central figure in the growth of marine geoscience in Atlantic Canada. Throughout his long self-employed career, his work became widely known and influential both nationally and internationally,” Mr. Piper wrote.

Howard Epstein, a retired lawyer and former Halifax city councillor and MLA, brought Mr. Ruffman in to co-instruct in his course on land-use planning law at Dalhousie. “Alan was a non-stop talker,” Mr. Epstein wrote in a Facebook tribute. “His experience in fighting city hall was not just exemplary, but often much more successful than my own”

And on Jan. 10, the Halifax city council, often the target of Mr. Ruffman’s harshest criticism, paused to pay him tribute. Referring to him as “Citizen Ruffman,” councillor Patty Cuttell, a professional urban planner, recalled how he would often stop by her home to discuss planning and development issues. “He was passionate in his belief that community participation is the cornerstone of a successful city,” she told the council. “I feel very fortunate to have known him.”

Alan Stuart Ruffman was born on July 10, 1940, in Newmarket, Ont., and grew up in Richmond Hill. His father, Kenneth, was a salesman and a naval veteran who served on the HMCS Norsyd during the Second World War. His mother, Dorothy, worked at the Richmond Hill David Dunlap Observatory. (They divorced in 1956.)

Mr. Ruffman graduated from the University of Toronto Schools in 1959 and then attended Victoria College at the U of T, enrolling in an honours science course. He became president of his freshman class and involved himself in so many extracurricular activities that he failed his first year. Undaunted, he re-enrolled in the same course and graduated in 1964 with a BSc in geology and a National Research Council fellowship to study marine geoscience at Dalhousie University’s Institute of Oceanography in Halifax.

He had completed his Master of Science and was on his way to getting his doctorate when he was cautioned that he had to decide whether he was going to be an activist or a scientist. He chose to abandon his PhD but he continued his career as a marine geologist and urban activist, determined to prove that he could be both.

Mr. Ruffman’s first major scientific coup came when he persuaded the Deep Sea Drilling Project (the first of several international scientific seabed drilling programs started in 1968) to take core samples from a “bump” on the ocean floor about 550 kilometres northeast of Newfoundland. He named it “Orphan Knoll,” because he suspected it was an abandoned fragment of the continent from a time, about 100 million years ago, when the land masses of Europe and North American began to drift apart. The core sample proved his hunch right, and as a result, under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Canada was able to claim jurisdiction over another 70,000 square kilometres of seabed.

In 1973, with a colleague, John Stewart, he formed Geomarine Associates. Within a few years, the company had become Atlantic Canada’s most successful seafloor mapping company, with 32 employees, offices in St. John’s and Halifax, and major clients like Chevron and Mobil Oil. In 1985, the company divided, with Mr. Ruffman retaining the company name, its library of reports, and his office on Prince Street in Halifax.

Freed from the constraints of running a company, he pursued his investigations into historical disasters, both accidental and natural. In 1992, he organized a symposium to mark the 75th anniversary of the Halifax Harbour disaster when a ship loaded with munitions blew up, killing 2,000 and devastating much of the city’s waterfront. He co-edited Ground Zero, an anthology of contributions to the symposium that has since become a collector’s item.

Mr. Ruffman’s persistence and his ability to make inspired guesses led him to uncover two collections of lost drawings by Arthur Lismer, a member of the Group of Seven who had been an eyewitness to the Halifax Explosion.

He published a book of original research called The Titanic Remembered: The Unsinkable Ship and Halifax, and led a highly publicized investigation into the identity of several victims, including a small child drowned in the Titanic disaster and buried in Halifax’s Fairview Lawn Cemetery, hitherto known only as “Body No. 4.” Using mitochondrial DNA from several teeth and a tiny bone fragment that remained in the grave, Mr. Ruffman did the complex genealogical research that eventually, after an initial false result, led back to the child’s mother. His investigation was twice featured on the PBS series, “Secrets of the Dead.”

Mr. Ruffman’s studies of historical catastrophes like the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 or the tsunami that hit Newfoundland in 1929 are more than just technical accounts of long-forgotten disasters. Drawing on a variety of sources like ships’ logs, newspaper stories, diaries and journals, and eyewitness accounts, he was able to present a complex picture of their human and social impacts.

His title for a study of the greatest natural disaster to visit our shores is deceptively dry: “The Multidisciplinary Rediscovery and Tracking of The Great Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon Hurricane of September, 1775.” It’s a harrowing account of the superstorm that killed over 4,000 people two-and-a-half centuries ago. “There are good reasons to try to understand the full range of natural catastrophes that beset a nation from time to time,” he wrote. “By knowing the highest storm surge, strongest winds, thickest ice or highest wave height, we are better able to design societal barriers and emergency responses. … At one time storm deaths occurred almost entirely at sea. … Now such deaths are increasingly on the land, as more urban growth is located in low-lying coastal areas. The threat from catastrophic hurricanes and related storm surges is still real.”

Mr. Ruffman never lost his fascination with the life of his chosen city, Halifax. In an e-mail, Ms. Cuttell, the Halifax councillor, wrote that he was still showing up for council meetings shortly before he died. “Alan was a knowledge-keeper,”' she wrote, “and with his passing, a lot of local knowledge has been lost.”

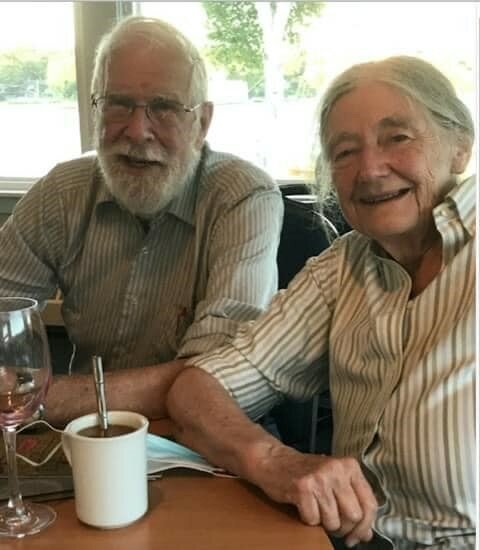

Mr. Ruffman leaves his wife, Linda Christiansen-Ruffman; sister, Gillian Danner; half-sister, Mag Ruffman; and half-brother, Ted Ruffman. Another half-brother, Gregory Williamson, is deceased.

One of the most poignant pieces of Mr. Ruffman’s legacy will remain, like Orphan Knoll, forever out of sight. Off the south coast of Newfoundland, near the site where the Titanic sank, there are seven undersea hills referred to collectively as the Fogo Seamounts. At Mr. Ruffman’s request, those features now have names: Algerine, Birma, Carpathia, Frankfurt, Mackay-Bennett, Montmagny, Mount Temple. They are the names of the ships that responded to the Titanic’s calls for help.

SERENITY

FUNERAL HOME

Serenity Funeral Home and Chapels

Monday to Friday 8:30 - 4:30

24/7 By Phone

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 679-2822

Fax: (902) 679-0424

NEW ROSS FUNERAL CHAPEL

New Ross Funeral Chapel:

By Appointment Only

4935 Hwy12,

New Ross, B0J 2M0

Mailing Address:

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 689-2961

Fax: (902) 679-0424

DIGBY COUNTY FUNERAL CHAPEL

↵

Digby County Funeral Chapel

By Appointment Only

367 Highway 303,

Digby, B0V 1A0

Mailing Address:

198 Coldbrook Village Park Drive, Coldbrook

N.S. B4R 1B9

Phone: (902) 245-2444

Fax: (902) 679-0424